I can remember doing two-a-day workouts with my basketball team that included relay suicide runs and sprints up a long hill. When we were waiting for our teammate to hand off or as we got to walk down the hill, coach would say, “Put your hands on your head” to help us recover faster and get our breathing to slow down. Personally, I never found that effective and now, 20-some years later, I know why.

Putting your hands on your head or behind your head is not an effective recovery position because of the posture it puts your ribcage and spine in.

When your chest is elevated and your spine is hyperextended, your diaphragm’s ability to move through its full range of motion is challenged and the respiratory mechanics are inefficient to recover quickly. Allow me to explain a little bit more…

A key part of recovery is relaxation. To get an overactive or tonic muscle to relax, it must lengthen. Your diaphragm muscle relaxes and lengthens when the ribs slide down, internally rotate, and retract back for the thoracic spine to flex. This ribcage posture better positions your respiratory mechanics to slow down, relax and recover faster than when your ribs are flared, elevated, and externally rotated with the spine extended.

Your diaphragm is your main breathing muscle and it, too, must move through a range of motion to lengthen and contract. Think about your biceps — if your bicep is contracted, your elbow will flex so that muscle can shorten. To get your bicep to relax and lengthen, you have to straighten your elbow.

Just like your elbow moves through a range of motion to influence the bicep, your thoracic spine and ribcage will move through a range of motion to influence how your diaphragm contracts and lengthens.

Your diaphragm lengthens and contracts up and down like a piston inside of your ribcage. When your ribs are down and the thoracic spine is rounded, the diaphragm is optimized to move with maximal efficiency.

When you place your hands on or behind your head, your thoracic cage gets elevated and pushed forward as your spine goes into extension and hyperinflation. This alters your natural spinal curve on the backside and will limit the movement for your diaphragm to move up and down.

Moreover, in most people, this position will activate the back muscles and over-lengthen or inhibit the abdominal muscles, which counteracts diaphragmatic support. Lastly, this position limits three-dimensional chest wall expansion because as the front ribs lift up, the back half of the ribs close and compress down, not allowing the back half of your chest wall to expand. All of which leads to less-effective respiratory mechanics.

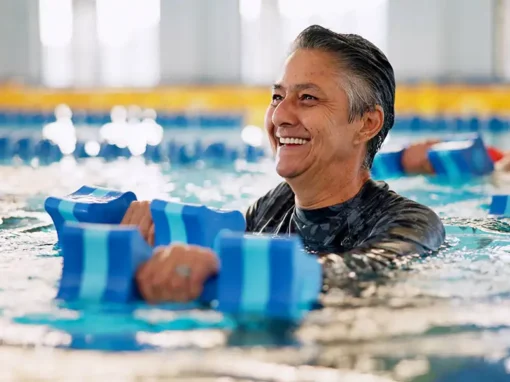

Hands on knees and rounded posture helps to keep the ribcage flexible, and allows for more three-dimensional chest wall expansion.

It also lengthens the back muscles and better positions the abdominal wall to support the diaphragmatic movement allowing for more effective respiratory mechanics. Your diaphragmatic movement is optimized with abdominal opposition when the back ribs are open and expanded.

A 2019 sports science study published in the Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine supports the understanding of how posture influences respiratory mechanics and recovery. The flexed posture of resting your hands on your knees is the better position when it comes to recovery.

This research study looked at college soccer players recovering from high- intensity interval training workouts. The soccer players had three minutes to recover and were randomly designated a recovery posture — either a hands-on-head or hands-on-knees position.

This study confirmed that the hands-on-knees position resulted in a significantly faster recovery, faster decrease in heart rate, greater elimination of carbon dioxide, and improved movement of air in and out of the lungs between intervals than the old-school hands-on-head notion.

Effects of Two Different Recovery Postures during High-Intensity Interval Training

Author: Joana V. Michaelson, Lorrie R. Brilla, David N. Suprak, et al

Publication: Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine

Publisher: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Date: Feb 15, 2019

Copyright © 2019, Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the American College of Sports Medicine.

An expert source on the translation of science to action, the Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine (TJACSM) is a peer-reviewed journal of the American College of Sports Medicine publishing original research, clinical trials, systematic review articles, and meta-analysis and policy research that discuss the translational implications of basic, clinical, and policy science to everyday real-world practice.

Effective and efficient respiratory mechanics requires a flexible ribcage to support posture and diaphragmatic movement. When you are having difficulty breathing, do not hyperextend, lock up and lift your ribcage more. This may seem counterintuitive if you don’t understand how the diaphragm needs to moves up to relax inside of a deflated ribcage. Instead — slow your breathing by rounding your back and resting your hands on your knees.

The ability to recover faster from high-intensity training is an important factor for optimizing athletic performance. Faster recovery and improved breathing can help to conserve energy and reduce potential injuries due to taxed muscles and altered mechanics from fatigue.